The Bluffton–Savannah Hurricane Dead-Zone: Myth, History, and Risk

The Bluffton–Savannah region is often thought of as a hurricane “dead-zone” thanks to decades without a direct strike, but history shows devastating storms have hit before. The apparent protection is mostly due to steering patterns and chance, while the concave Georgia Bight actually heightens storm surge risk when hurricanes approach.

Background – Why Savannah and Bluffton Are Seen as a “Dead‑Zone”

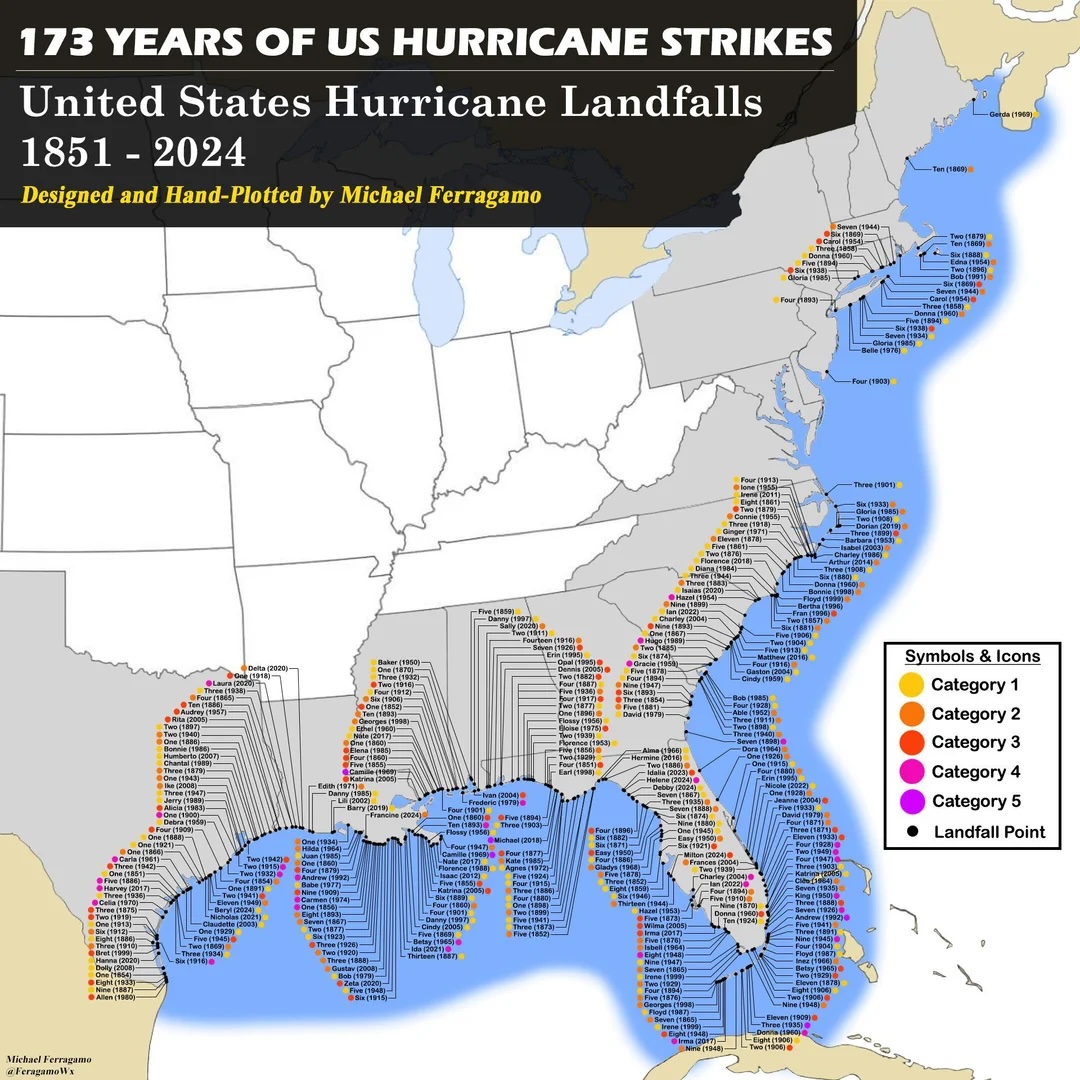

USA TODAY’s map of Atlantic hurricane landfalls highlights a surprising gap—no hurricanes have crossed the coastline between roughly New Jersey and Virginia since 1903 because the shoreline points north–south and strong upper‑level winds often steer storms east back into the Atlantic. Many locals in the southeastern U.S. see a similar “dead‑zone” around the concave Georgia Bight—the stretch of coast from Cape Fear, North Carolina, down past Hilton Head and Savannah to Cape Canaveral. People in Bluffton, Savannah and the Golden Isles sometimes say the bight’s inward curve protects them from hurricanes; Savannah is even nicknamed “Dodge City.” However, meteorologists and historians note this supposed shelter is mostly luck and may breed dangerous complacency.

How the Georgia Bight Influences Storm Tracks

Curved coastline and the Bermuda High: The Georgia coast curves inland, meaning storms moving north from the tropics encounter a shoreline angled northwest. When the Bermuda High, a large summertime high‑pressure system in the Atlantic, is in its usual position, its clockwise circulation tends to steer storms to the northeast, causing many hurricanes to recurve offshore before reaching Georgia. Dr. Marshall Shepherd of the University of Georgia notes that this circulation has helped spare the state a land‑falling hurricane for over a century, but he warns it is not a permanent shield. The shape of the coastline means storms are more likely to skirt the shore or hit elsewhere rather than making a perpendicular impact.

Concave coast amplifies surge: Coastal geologists caution that the inward curve of the Georgia Bight and its wide, shallow continental shelf can actually amplify storm surge. A report for the St. Marys Flood Resiliency Project explains that the concave configuration, shallow shelf and large tidal range give the potential for very large storm surges even though hurricanes have been infrequent in the 20th century. Geological evidence shows that major hurricanes impacted the Georgia coast repeatedly over thousands of years, so the recent quiet period is not the norm.

Historical Context – Notable Landfalls in the Bluffton–Savannah Region

Although the last century has been quiet, historical records show major hurricanes striking the region in the 19th and early 20th centuries:

| Year & Name | Impact on Bluffton/Savannah | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Aug 27–28 1893 – Sea Islands Hurricane (Cat 3) | Made landfall just south of Savannah with ~115 mph winds. Produced a storm tide ~16 ft and inundated the low‑lying Sea Islands, killing at least 1,000–2,000 people and destroying communities on Hilton Head Island and other islands. The disaster is regarded as one of the deadliest U.S. hurricanes; Savannah was spared total flooding but lost rice plantations and phosphate works. | National Weather Service (NWS) chronicles of the Sea Islands hurricane. |

| Oct 1–3 1898 – Cumberland Island Hurricane (Cat 4) | Landfall near Cumberland Island (south of Savannah) with a storm tide near 20 ft. It devastated coastal Georgia, killed 179 people and flooded areas even near Savannah. | NWS tropical cyclone history. |

| Sept 4 1979 – Hurricane David (Cat 2 at landfall) | Made landfall near Black Beard Island, GA; the eye crossed the Savannah metro area, making David the last hurricane to directly hit Savannah. Observed winds were 58 mph sustained at Savannah airport (gusts to 70 mph at Hilton Head) and widespread power outages lasted weeks. | NWS public information statement for the 35th anniversary. |

Other entries in the NWS records show multiple 19th‑century hurricanes hitting Hilton Head and the Savannah area, including an 1881 storm that killed about 700 people and a 1911 Cat 2 hurricane. These storms illustrate that the “dead‑zone” is a modern phenomenon rather than a long‑term pattern.

Near Misses and Surge Flooding in Recent Decades

Since 1979, the Bluffton–Savannah region has experienced several near‑miss hurricanes that, despite not making landfall, inflicted significant damage:

Hurricane Matthew (2016) – The eye passed ~20 mi offshore but produced the highest tide ever recorded at Fort Pulaski (12.56 ft), flooding much of Hilton Head Island and Beaufort County and causing widespread tree damage.

Tropical Storm Irma (2017) – Arrived at high tide, pushing 12.24 ft of water at Fort Pulaski (second‑highest recorded). Downtown Savannah’s River Street flooded, and winds gusted over 60 mph.

More than luck? – A SavannahNow article in 2024 notes that Savannah has not had a direct hit since 1979, earning the “Dodge City” nickname, but experts warn this luck could change. They point out that Georgia’s shorter coastline and location between Florida and the Carolinas provide some shielding, yet climate change and shifting storm tracks could increase risk. The same article stresses that the lack of recent landfalls breeds complacency and that no permanent geographic advantage exists.

Why Fewer Landfalls Since 1900?

Meteorologists cite several factors for the apparent lull:

Prevailing steering patterns: The Bermuda High often deflects Atlantic hurricanes northward; storms then either curve out to sea or hit the Carolinas instead of Georgia. When the high shifts west, storms can move into the Gulf of Mexico or make landfall farther south.

Randomness and small coastline: Georgia’s coastline is only ~100 miles long. Many hurricanes pass just north or south of this segment; a small shift in track can be the difference between a direct hit and a near miss. Climatologists emphasise that the gap is largely due to statistical chance rather than protection.

Misconception of the bight’s protection: Interviews in coastal Georgia reveal that many residents believe the bight deflects hurricanes. Research from the St. Marys Flood Resiliency project found this perception is inaccurate; the area remains vulnerable and educational outreach is needed. The same report notes that the concave coast and shallow shelf can amplify storm surge, making the region more susceptible to flooding.

Implications for Bluffton and Savannah Residents

Don’t assume immunity: The long quiet stretch does not mean the area is safe. Major hurricanes have struck before, and the physical factors that steered storms away may change. Residents should view the gap as luck, not protection.

Storm surge risk: Because the coastline is concave and the shelf is shallow, storm surge can be extreme even from storms that do not make landfall. Irma and Matthew demonstrated that high tides combined with winds can flood downtown areas and barrier islands.

Prepare for future climate: Warmer oceans and shifting atmospheric patterns could alter storm tracks. The SavannahNow article warns that climate change may increase Georgia’s hurricane risk and emphasises that no permanent geographic advantage exists. Residents should maintain evacuation plans and heed emergency management guidance.

Conclusion

The Bluffton–Savannah “dead‑zone” is a real pattern in the historical record—no hurricanes have made landfall there since Hurricane David in 1979. However, history shows that the region has experienced catastrophic hurricanes, and the apparent protection is due to prevailing steering patterns and statistical chance. The concave Georgia Bight does not shield the coast; it actually makes storm surge worse. Recent near misses like Matthew and Irma show how damaging surge and flooding can be without a direct hit. Residents of Bluffton, Savannah and surrounding communities should respect the power of hurricanes, remain prepared, and not rely on the myth of a permanent “dead‑zone.”